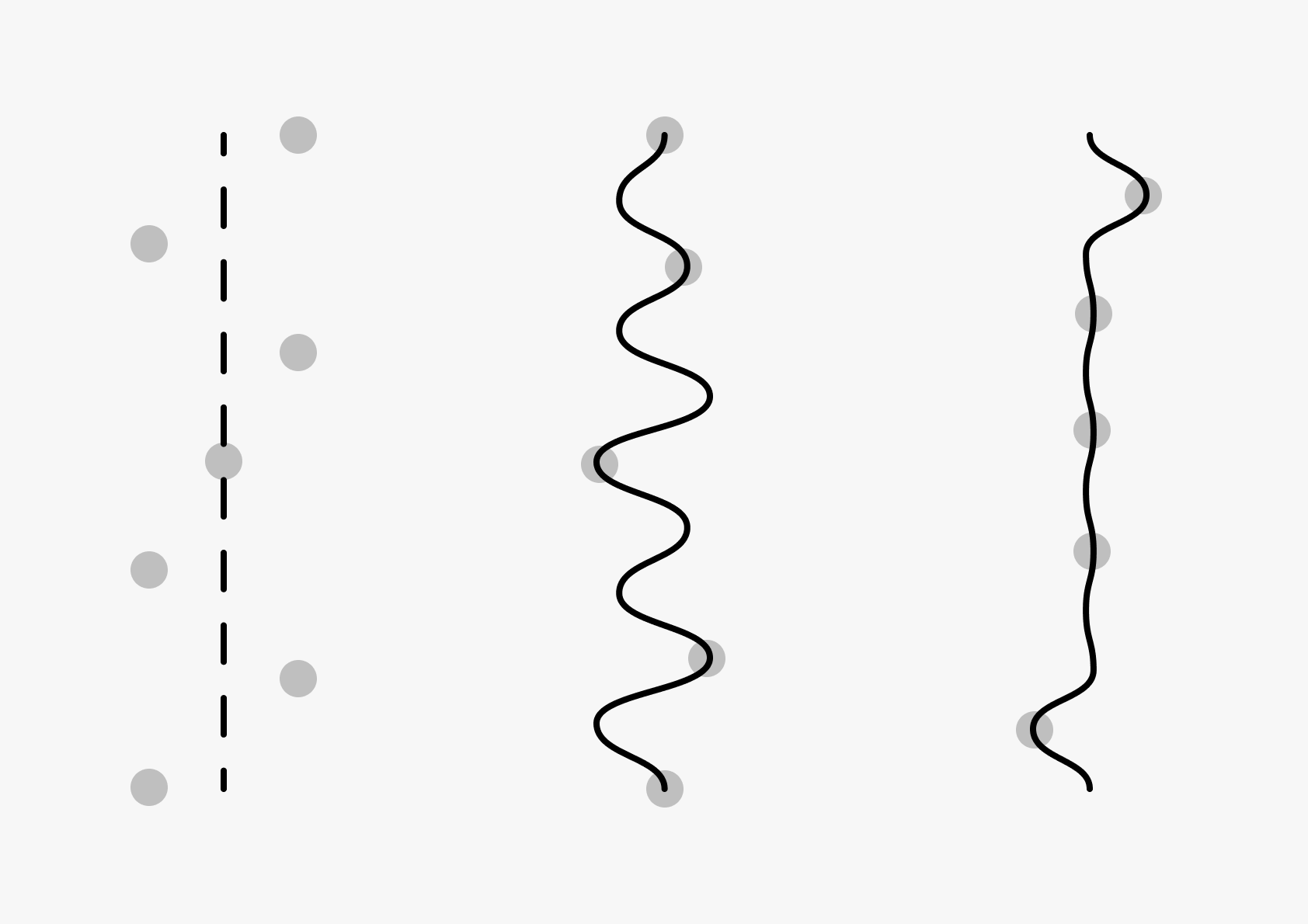

Illusion of alignment

Doing more than describing actions

Approx. 5 mins to readI’ve been in countless meetings where people set lofty goals and through numerous weeks-long sessions devoted to OKRs or whatever trend du jour happens to have swept the business world. I’ve similarly sat through many updates devoted to reporting progress against those goals only to see them at best given lip service and at worst completely ignored.

I’ve witnessed the countless very creative ways that people ignore goals, but I’m going to focus on three phases that stand out (for readers hoping for a happy ending, the third and final stage is intended to be just that). If you’ve worked inside a slightly dysfunctional organisation before (hint: you have, it’s all of them), they’ll be very easy to spot.

- Describing actions, ignoring goals

- Bending goals to match the actions

- Aligning actions with the goals

Describing actions, ignoring goals

This phase is the most insidious, because it feels great without actually being great; akin to the brainstorming session that leaves everyone very excited but in no way closer to the decision they were trying to make. People talk about project after project that’s in-progress, shipped, or very-nearly-but-not-quite-ready (repeated ad nauseam).

People might reference the goal at the beginning of the update, at the end, or somewhere in the middle (when they remember that they ought to), but the words that come afterwards leave you wondering why they bothered. I should note that it’s still best to assume positive intent here—working on hard problems is hard; blame the system, not the person.

If you’re subjected to an update like this, you’re well within your rights to ask as often as feels necessary how that project will positively impact [goal]; how it will move the numbers that need to be moved. It should be done tactfully, of course, but not so softly that it feels like a general inquiry into the state of things out of personal [dis]interest.

Describing actions devoid of the reason for doing them is motion when you’re looking for progress. They feel much the same in the moment, but when your bum hits your seat again and you reflect, it becomes startlingly obvious that they are different in ways that shouldn’t be ignored. Erosion can go unnoticed until the cliff one day falls into the sea.

Bending goals to match the actions

If the first phase is the most insidious, this one is the most nefarious. Ignorance is often excusable because it’s just that—no one set out to ignore the goals, but there wasn’t enough friction to keep things aligned and so they started to drift. Bending the goals is active, and if done either repeatedly or dramatically undermines the point of them.

Like the frog boiled alive for failing to notice the gradual changes in temperature, goals slowly get adjusted to match actions that were already happening. I’m not talking of the case where new information supports a restating of the goals—that can and should happen when required. I’m talking of the case where existing actions are unchanged by new goals.

Actions left unchanged by new information is unchecked inertia, and it can be tricky to spot for the same reasons given in the first phase: things are happening; people are working. Additionally, though, it’s less obvious on reflection that something is wrong. The actions reported appear to match the stated goal, it’s just that the goal isn’t right.

In part I’ve seen this solved by a couple of things: being excruciatingly clear about the numbers that need to move and talking first and foremost about those numbers, rather than some abstraction, and; keeping the number of goals small and not having a waterfall of goals flowing through every function, team, and person such that they’re overly abstract.

Aligning actions with the goals

This is quite a jump, but the phases leading up to here look and feel a lot like the first two phases. This final phase is the one that we think that we’re in most of the time (and want to be in all of the time), but unless we’re reminded of it on a daily basis, are probably pretty far from. Sticking to goals is hard—if it wasn’t, we’d do it all the time.

When actions are aligned with goals, it’s repeatedly and very specifically clear. People state the goal, walk through the actions, and very clearly point to the moments that the numbers moved in the right direction as a result of them (hopefully, but it’s still very good to know when a specific action moved numbers in the wrong direction).

If you’re in this phase, when you ask why some action is being taken, people can quickly and accurately articulate what good thing will happen as a result of it and what bad thing might have happened had it not been taken; the benefit of doing the work and the opportunity cost associated with doing this thing and not the next best thing.

It’s important to note here that you probably won’t have (and to some extent shouldn’t aim for) 100% alignment. It’s good to pursue goals, but it’s also good to acknowledge that the goals are never perfect. Allow space for ideas that are very likely to fail and which are not obvious when planning for the next sprint, quarter, or whatever.

The next time you’re either creating goals or in some session to review them, observe carefully and try to evaluate which of these phases you might be in (you could, of course, be in none of them—in which case attempt to describe what you see and write your own post so that we’re all better prepared).

Apr 25, 2020